THE WORLD : SOUTH ASIA

|

THE WORLD : SOUTH ASIA |

|

The World in 2000 | Africa | Central America And The Caribbean | North America | South America | Antarctica

Central Asia | Eastern And South-Eastern Asia | South Asia | Europe | The Middle East | Oceania

Timeline | Differences | Politics | Science and Technology | Society | Notes | Summary | Home

This page is divided into the following sections:

Click on the section names to return to the top of the page.

Over the years many people have travelled to India to seek their fortunes there, much as they did in the real world during colonial times. In this world, however, rather than looting the wealth of a weak and divided India and shipping it back to their home countries, they have sought their advancement by immigrating into and working for the benefit of the success story of a strong India.

The Indian Ocean is very much under the control of the Indian nations, particularly the Dakshina Nad. South-East Asia, Marege [Australia] and eastern Africa all fall within the sphere of influence of the Indian nations.

The only rival to the Mughal Empire on the Indian sub-continent, and indeed the only other nation there, the Dakshina Nad is a federation of Southern Indian and other states spread around the Indian Ocean and south-east Asia that has evolved out of the Kanyakumari Pact, a defensive alliance formed in 1697 to protect the states of southern India against the expansion of the less aggressive [without Aurangzeb] but still threatening Mughal Empire to their north. In overall organisation the Dakshina Nad is a Thalassocracy, a state with primarily maritime realms. It has a population of more than five hundred million people.

Although officially known as the Kanyakumari Federation, the more commonly used name of the nation, the Dakshina Nad, has grown out of the traditional term for South India, with Dakshina meaning 'south' and Nad meaning 'land'. It is also occasionally known as the Dravida Nad or simply Dravida.

The Kanyakumari Federation is a federal government with elements similar to that of Switzerland of the real world. Its administrative capital (roughly equivalent to Brussels in the European Union) is the city of Kanyakumari at the very southern tip of India, in the separate Federal District of Kanyakumari. It is here that the original Kanyakumari Pact was signed in 1697, and where the Kanyakumari Federation was formed in 1901 after long years of increasingly close cooperation for mutual protection against the Mughal Empire and other threats.

The government of the Dakshina Nad helps to coordinate projects that affect and/or span the entire Federation, such as the space programme, the Dakshina Nad Lace [internet], elements of the railway and transport network, and large international engineering efforts such as the Rama's Bridge project.

The Kanyakumari Pact was originally intended for defence alone. As such it allowed members to war among themselves, but also obliged them to allow other Pact forces to move through their territory in the event of war with the Mughal Empire. Over time and with the creation of the Kanyakumari Federation this has evolved into a fully united system.

Originally each Pact member was entirely responsible for their own laws and so on, though they were also obliged to tolerate the religious beliefs of visitors from other Pact nations, a consideration that was considered essential if people from all of the Pact nations were to be able to work together.

This remains largely the case today, although the Pact and later the Federation have taken over elements of external economic policy and also of defence, unifying the navies of the states of the Dakshina Nad in 1760, and their armies and air forces on the creation of the Kanyakumari Federation in 1901.

Over time the Dakshina Nad political system has taken on board many political concepts originating in Europe. The merging of these two sets of political concepts have gradually, and not without problems, formed a political system as effective as, if different from, any of the political systems of the real world.

The royal families of the states making up the Kanyakumari Federation (where they exist) each retain their position in their home state. In addition, the position of head of state of the Federation rotates among each of the leaders of the constituent states in turn on a two year basis [this is similar to the Majlis Raja-Raja system in Malaysia in the real world].

The Vai Arasan (Tamil for Assembly of Kings) made up of representatives of the monarchs and nobility of all of the states of the Federation acts as an advisory council in the Federation, performing a similar function to the durbars of the individual states. The Ashta Pradhan, derived from the Maratha council of the same name, forms a council of ministers for the Kanyakumari Federation in parallel with this.

Most of the governments of the Dakshina Nad use similar organisations, such as Navaratnas, at a more local level, and most have at least some form of parliamentary system.

The politics of the Dakshina Nad, and indeed of all of India remain based on tribal and geographic boundaries, as they have been for centuries, rather than on peoples identification with and alignment to their religion [as happened due to the actions of the Emperor Aurangzeb in the real world].

The Dakshina Nad is lacking in coal so it has long made use of hydroelectricity, wind power, and nuclear power to drive its industry instead. The Dakshina Nad leads the world in space and in space technology.

There are a number of powerful companies in the Dakshina Nad. These are roughly similar to the Tayefe Karkhanas of the Mughal Empire, and are known as Kulam Thoyil Kadai (Family Workshops). These have varying degrees of political power in the different states of the Dakshina Nad.

Both sides of the border between the Dakshina Nad and the Mughal Empire are dotted with fortresses built to defend against the other side in the eighteenth century and often upgraded in the nineteenth century. In the present time these fortresses remain as picturesque tourist attractions.

The Dakshina Nad and the Mughal Empire are linked by an extensive network of roads and railway lines.

The official language of the Dakshina Nad is Tamil, although many other languages are spoken across the regions it controls. Telugu is the second most commonly-used language in the Dakshina Nad. Because of this most popular writing in the Dakshina Nad is in Tamil and Telugu, although there is much published work in other local languages.

The Dakshina Nad officially uses the Hindu Calendar, though a different version to that used in the Mughal Empire. The Islamic, Buddhist and Christian calendars are also widely used, the latter particularly in the Philippines.

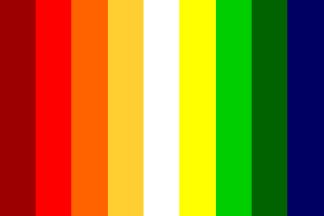

The flag of the Dakshina Nad consists of nine vertical stripes in colours derived from the national colours of all of the states in the Kanyakumari Pact, and from the major religions of all of the peoples within it.

The currency of the Dakshina Nad is the Kanyakumari Rupee, first issued in 1744 after the unification of the various currencies of the states making up the Kanyakumari Pact. This currency remains distinct from the Mughal Rupee.

When the members of the Kanyakumari Pact unified their currencies into one, a law permitting the free movement of labour within the Kanyakumari Pact also came into effect. Over time this law has acted to eliminate the worst excesses of the governments of the Dakshina Nad states as people have tended to vote with their feet to escape bad government. By the present day many of the states have, out of self-interest, evolved into enlightened absolute monarchies.

The Hindu caste system still exists within the Dakshina Nad, although it has been weakened over time by the actions of the Sikhs and the example of the Mughal Empire. The strictness with which the caste system is applied varies from state to state within the Dakshina Nad, from quite strictly in Thanjavur to not at all in Pudhiya Kozhikode. In none of the states of the Dakshina Nad is it an entirely insurmountable barrier to individual progress or achievement, with economic and social mobility being entirely accepted.

The special forces of the Dakshina Nad have come, over the years, to be known as the Rakshasas, after the Hindu demons of the same name.

Along with others, the Nair make up a significant percentage of the armed forces of the Dakshina Nad, and of Pudhiya Kozhikode in particular.

The success of the Kanyakumari Pact and the Kanyakumari Federation has inspired other nations around the world to adopt similar forms of government. In particular the Banten Pact which led to the formation of Sarekat.

There are a number of world-renowned universities in the Dakshina Nad. In particular the universities of Mysore, Kandy, Kanyakumari and Manila are very well respected.

The nations of the Kanyakumari Federation in the year 2000 consist of the following:

The under-populated and undeveloped Antarctic territory of Thañnîr Nad remains a colony rather than a full member of the Kanyakumari Federation, although it is hoped it will become so in the future.

The Dakshina Nad has invited a number of other states, such as Ayutthaya, Dai Ngu, Sarekat and the Republic of Samudra to join it over the years. However so far they have all declined these invitations, some out a wish to maintain their independence, others under pressure from other nations, generally the Mughal Empire, and some from a combination of these.

Other nations, such as Bama and Brunei, are interested in joining, but the Dakshina Nad does not consider their political and/or economic situation to be conducive to their doing so.

The Mughal Empire is a large nation covering the north of the Indian sub-continent and stretching into Central Asia. Its southern border is a line across the Indian sub-continent from roughly Baroda in the west to Cuttack in the east. In the north it covers real world Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tibet, and parts of Central Asia. It also controls Tashkent and the great mineral resources south-east of it. The Mughal Empire is a world-class super-power, the most powerful individual nation on Earth (although it could not withstand all of the other nations on Earth at once, or even a subset of them), with a population of over a billion people. At least in part because of this there are significant Mughal expatriate populations in many parts of the world, particularly the Middle East.

The current Mughal Emperor is Salim Jahangir III, who has ruled since 1980.

The Mughal Emperors rule from the Peacock Throne in Delhi. Over time the term Peacock Throne has come to refer to the Mughal monarchy itself, as well as just their seat. [In this world the throne is never stolen by the Persian Nadir Shah in 1739 and remains in Delhi; as such it remains associated with the Mughal rather than the Persian royal family.] The continued presence of the Peacock Throne in Delhi means that the Koh-i-Noor diamond which forms part of the Peacock Throne also remains in the possession of the Mughal royal family as it has done since the founding of the Mughal Empire.

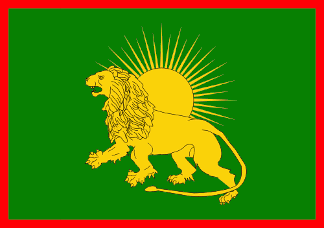

The flag of the Mughal Empire is a traditional design known as the alam, consisting of a green field with a red border centred on which is a golden rising sun partially eclipsed by a couching golden lion facing the hoist of the flag. [This is an evolution of the design of the real world, with the shape and exact colours of the flag having been modernised over time.]

The currency of the Mughal Empire is the Mughal Rupee [not unlike that of the real world from the period]. This currency remains distinct from the Kanyakumari (Dakshina Nad) Rupee.

In the Mughal Empire there are various '-abad's, cities named after emperors, in the spirit of Shahjehanabad.

Many Mughal cities, particularly the ones in which there are royal palaces, are very well-designed, with a minimum of slums and the like. Of course, other less prestigious cities are less attractive and have more obvious slums. But in most cities there are at least some public and private parks and gardens, designed with great care as peaceful havens in the city, and continuing and expanding the Mughal tradition of fine gardens. In particular the huge and magnificent Alambagh [Garden of the World] in Delhi is famed around the world. [For more on Mughal gardens see here.] Over the years Mughal gardens have come to incorporate elements from gardens around the world, as well as influencing gardens around the world. In particular a number of Mughal gardens contain elaborate follies inspired by those erected in Europe.

From the early days of the Mughal Empire many Mughal women have been as well educated as Mughal men. Over the years many Muslim women have been patrons of literature and themselves noted writers, poetesses, philosophers, scientists and so on.

There has long been some tension in the Mughal Empire between the cosmopolitan, multi-religious, multi-ethnic south and the much more mono-cultural and Islamic north. However, this has never become a serious issue in the Empire.

DELHI

The capital of the Mughal Empire is the vast and teeming city of Delhi, which lies on the Yamuna River. It is from here that the Mughal Emperor reigns from his palace, the Lal Qil'ah (Red Fort), built by the Emperor Shah Jehan and used by his descendants ever since [though it is significantly larger than and different to its real world equivalent due to the very different history of Delhi in this world]. Originally separate from the city, as part of Shah Jahan's new capital of Shahjahanabad, the Lal Qil'ah and Shahjahanabad itself now lie entirely within the bounds of Delhi, with Shahjahanabad as a suburb of the city.

Delhi has the most extensive underground railway system in the world, though as with much of the infrastructure of the Mughal Empire this actually consists of a number of largely independent systems running to and from different parts of the Delhi region.

One of the largest suburbs of Delhi is the area known as Firingi Pura (Foreigners Town). Originally built outside of Delhi to house Europeans who took service with the Mughals, it is now home to a broad cross-section of Mughal society, though it is no longer the prestigious district it has been in the past. There is also much modern construction in the vicinity of, and into, the Delhi Ridge, particularly blockhouses and bunkers intended to provide resistance to damage during the Long War.

Delhi is home to a number of famous examples of Mughal architecture. In particular, the Lal Qil'ah itself and the Delhi Pantheon, completed in 1815 as a Temple of All Faiths and intended to show that the Mughal Empire is tolerant of and welcoming to people of all faiths, and thus superior to the nations in which religious intolerance has caused so many problems. Delhi is also home to the huge and magnificent Alambagh [Garden of the World], a vast public gardens constructed in the Mughal style.

Delhi also contains a large number of the mansions known as Havelis. Some of these date back centuries, while others date from more recent years. Even the older havelis have been extended and updated in more modern styles. Although still going by the same name, because of limitations of space and cost, new havelis are often smaller than older ones, many even lacking the central courtyard that was once considered an essential feature of their design.

Many of the havelis of Delhi, and in recent times many other buildings, have underground levels known as tykhanas which provide cool accommodation during the blazing Delhi summer. These have been adopted in hotter climates elsewhere around the world. Again because of the heat of summer Delhi is the city with highest density of air conditioning in the world, and the mechanical air conditioner was invented there in 1802, with electrical systems following in 1816. In some parts of Delhi, particularly the more commercial areas, whole swathes of buildings are linked by air conditioned tunnels and covered bridges, allowing people to about the area in comfort.

Delhi has a population of some ten million people [actually smaller than the Delhi of the real world, though spread over a larger area, and with India as a whole having a larger population].

Delhi is home to a number of world-renowned universities and religious schools.

AGRA

The second city of the Mughal Empire is Agra, also on the Yamuna River. The city has its own older Lal Qil'ah (Red Fort), from who the Mughal Emperors reigned before the capital moved to Delhi. Agra is best known for the two Taj's there, the Taj Mahal, erected by Shaj Jehan to commemorate his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and the Taj Jehan, erected by Emperor Shah Buland Iqbal [Dara Shikoh] to commemorate his father and which is a mirror of it, but in black marble rather than white, facing the Taj Mahal from the other side of the Yamuna river. It is also known for the magnificant tomb built by Emperor Shah Buland Iqbal for his beloved sister Janhanara Begum.

SRINAGAR

A city in the Kashmir Valley of north India, connected to the rest of the Mughal Empire by extensive rail and other transport links. It has been the Mughal summer capital for centuries, the place where much of the court, and those of rest of the Delhi population who can afford it, moves to escape the oppressive heat, humidity and rainfall of the Delhi summer.

Because of its being the summer capital, Srinagar is very quiet for much of the rest of the year. This, combined with the desire of the Mughal Emperors to keep Srinagar a relatively un-crowded place to spend their summers has limited the growth of the city, so that it has a permanent population of some two hundred thousand people [as compared to more than a million in the real world], which grows to at least double that in the summer.

The majority of the economy of Srinagar is based on the visitors who come in the summer, along with a smaller number who come in the winter for activities such as skiing. Agriculture and textile production make up much of the rest of the economy of the city.

The city is well known for its magnificent palaces and gardens, many of the latter built on the orders of the Mughal Emperors down the centuries. Holidaying on houseboats on the Dal Lake that adjoins the city is very popular.

[Srinagar, and the Kashmir valley in general, has a quite different history to the real world, but parts of the city and its surrounds would still be recognisable.]

KABUL

A teeming industrialised metropolis of more than two million people, with extensive rail (via the Delhi - Rawalpindi - Kabul - Samarkand line) and road connections (via the Grand Trunk Road) to the rest of the Mughal Empire, Kabul is the third city of the Mughal Empire (after Delhi and Agra). When staying in the city the Mughal Royal Family themselves use what is known as the Qasr Sabz [Green Palace in Persian], a massive complex built of Afghan green marble in roughly the same location as the Tajbeg Palace of the real world, but much larger and more impressive than it.

Centuries as part of the heart of the Mughal Empire since the conquest of the city by Babur, the first Mughal emperor, in 1504 mean that the city has a rich cultural and historical background. This long and relatively stable history means that the city has a well-developed infrastructure able, with the help of reservoirs in the mountains, qanats and piped water, to support a large population despite its dry climate.

Ever since the discovery of the rich mineral resources of Afghanistan [much earlier than in the real world where they were not really recognised until the 1980s or later] there has been extensive mining and associated industrialisation in Kabul and its vicinity. Many of the Mughal Tayefe Karkhanas have facilities within or around Kabul.

Although predominantly Muslim, the population of Kabul also includes a significant minority of other religions, in particular Hindus and Sikhs, and the city is home to a number of major mosques, temples and Gurdwaras.

Home to two world-renowned universities, Kabul is also the centre of Pashtun literature, and especially of those writers who look back to the wild times before the Mughal conquest with romanticised nostalgia.

The Kabulistan Museum in the city, the first public museum in the Mughal Empire, was originally intended to commemorate the Emperor Babur and was built adjacent to the Bagh-e Babur [Gardens of Babur] that were built on his orders. Since then, however, it has expanded into a vast complex of exhibitions and displays detailing in particular the history and archaeology of Afghanistan and Central Asia, which are much better understood in this world than in the real world.

[Kabul as a whole has an utterly different recent history in this world to that in the real world, leading to its being almost unrecognisable here. Only some of the older parts of the city, such as the Gardens of Babur, and the shapes of the surrounding mountains, remain recognisable between the two.]

SAMARKAND

The northern end of the Delhi - Rawalpindi - Kabul - Samarkand railway line and the last major city before the northern border of the Mughal Empire where it meets the states of Central Asia, Samarkand was conquered by the Mughals in 1678 and has remained part of the Mughal Empire ever since. It is known as the fifth city of the Empire, with the nickname of the Blue City because of the great use of that colour on its buildings. It has a population more than a million people.

The economy of the city is mostly based on agriculture and its associated industries. However, the city is also a centre of trade with the khanates and other nations of Central Asia, and railway lines lead across the Mughal border to facilitate this.

As in Kabul, although predominantly Muslim, the population of Samarkand also includes a significant minority of other religions, in particular Hindus and Sikhs, and the city is home to a number of major mosques, temples and Gurdwaras.

Because of its proximity to the northern Mughal border, and so to the Holy Russian Empire, Samarkand became increasingly militarised over the course of the Long War, with a number of airfields, military barracks and training facilities, as well as maintenance facilities growing up on the fringes of the city. Another effect of the Long War was the growth of a number of shanty towns around the city, where those displaced by the war, from within and without the Mughal Empire, came to live. Squalid and nests of crime, with the end of the Long War efforts are being made to clear or at least improve these slums and reduce the crime that occurs there.

The Bagh-e Buland Iqbal and its associated mosque, built near the Registan to commemorate the conquest of the city by the Mughals, was a popular place of pilgrimage in the Long War, particularly by soldiers.

There is no Russian influence in the city [unlike the case in the real world, where it was conquered by the Russians in 1868], but it is very heavily influenced by Mughal styles.

[Samarkand as a whole has an utterly different recent history in this world to that in the real world, leading to its being almost unrecognisable here. Only some of the older parts of the city, such as the Registan, remain recognisable between the two.]

ANDIJAN

A small town in the Fergana Valley within the Mughal Empire but close to its northern border [some 610 km east-north-east of Samarkand], Andijan is known to the outside world only because it is the birthplace of Babur, the first Mughal Emperor. As such it has a significant tourism industry, which has increased since the end of the Long War, and more transport links to the rest of the Mughal Empire than a town of its size might otherwise possess.

The politics of the Mughal Empire, and indeed of all of India, remain based on tribal and geographic boundaries, as they have been for centuries, rather than on peoples identification with and alignment to their religion [as happened due to the actions of the Emperor Aurangzeb in the real world].

[Note that the following is not exactly how these things worked in the historical Mughal Empire of the real world. Instead they are derived from that system with three hundred years of additional evolution and different history having acted to change it. Much of this is derived from this.]

The Mughal Empire is not a democracy. It is a form of oligarchic meritocracy based around the Mansabdar system, with a stable political structure which anyone who proves their merit can join, based on the results of the Imperial Examinations, based on the Chinese model and first instituted in 1699.

The four principal officers of the Mughal central government are:

In addition to this the Emperor will, when necessary, appoint a deputy known as the Vakil. Although to some extent the post is primarily for show and honour, the Vakil can also be handed those jobs beyond even the ability of the Diwan to complete.

In parallel with these posts is the Panchayat-i-Doulat, a ruling council, which advises these officials, and can also veto their actions and put forward ideas of their own if necessary.

The most significant changes to the Mughal system made to ensure the long-term stability and security of the Empire were those made by the Emperor Sultan Sipir Shikoh in 1709. These made changes to the Mansabdar system, including the introduction of hereditary positions, instituted a number of government-backed trading companies analogous to the state-owned Karkhanas (industrial concerns), and most importantly accepted restraints on the Emperors own power through the Kabir Manshur (Great Charter), which in Europe became known as the Mughal Magna Carta. Like the original Magna Carta this had the Emperor renounce certain rights, respect certain legal procedures and accept that the will of the Emperor can be bound by law.

Since then the Mughal political system has taken on board many political concepts originating in Europe and elsewhere. The merging of these different sets of political concepts have, in time, and not without problems, formed a political system as effective as, if different from, any of the political systems of the real world.

The Mughal system is a stable and efficient one with its officers chosen on merit, usually on the basis of their results in the Imperial Examination system. Mughal rulers and their officials have long had to live up to defined moral standards which give coherence to the administration and which they share - to varying extents - with most of their subjects. In effect the Mughal Empire is a constitutional monarchy.

The organization of all public services in the Mughal Empire is based on the Mansabdari system, borrowed originally from Persia. Every important officer of state in the Mughal Empire holds a Mansab (an official appointment of rank and emoluments), and, as a member of an Imperial cadre, is liable for service anywhere in the Empire. There are thirty-five grades of Mansabdar [in the real world there were thirty-three, but in this world the expansion of the empire has expanded the number of ranks], ranging from commanders of ten to commanders of one million.

Together, the ranks of the Mansabdars form a single unified Empire-wide military-bureaucratic hierarchy that includes both the military and the civilian bureaucracy of the Empire, underpinning the entire Mughal Civil Service. This provides cohesion and unity to the Mughal Empire and has done so for hundreds of years. Because of the military origin of the Mansabdar system the Mughal Empire could be considered to be a (generally benevolent) police state.

Each grade of Mansabdar carries a definite rate of pay, out of which the holders are required to maintain a quota of equipment [unlike the Jagir system that was used in the early days of the Empire]. This is strictly regulated to avoid the corruption that occurred in the early days of the Empire, but also sufficiently generous to ensure that the Mansabdar system attracts the ablest and most ambitious individuals from the whole of the Empire.

Mansabdars are appointed by the Emperor, originally on the recommendation of military leaders, provincial governors, or court officials, but since 1699 also on the basis of the results of the Imperial Examinations.

As individuals may re-apply for the examinations without any stigma, the class known as Ahadis, those not fortunate enough to secure a Mansab on their first application but who were employed in posts in the palace to be given an opportunity to show their worth, from which they could then be promoted to the ranks of Mansabdar, has withered and died over the years.

Because of its success and stability, the Mughal Empire becomes an exemplar for other regimes around the world [much like the USA of the real world]. It is also the land of opportunity. So others imitate it and its government, society and so on.

The Mughal nobility is a very mixed group, consisting, by the present day, of people of Indian and foreign descent of all types, classes and castes. These include those who have inherited a title or position, such as people of Rajput descent, as well as those who have made a place for themselves by their own merit.

All of the regions of the Mughal Empire are organised and run as Subahs (provinces), as are the various conquests that have been incorporated into the Empire over time, such as the Indian regions, Afghanistan, Samarkand, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet and so on. Mughal colonies are run in just the same way as other regions of the Empire, with the same governmental structures and so on, and less tax being levied as the place is being developed and more military presence as required. Places under military occupation are likewise run in a similar manner.

Local administration of all parts of the Mughal Empire is performed using a uniform administrative structure and set of procedures, with minor modifications to suit local conditions. Each Subah is headed by a governor, the Nizam or Subahdar. In parallel with the Nizam, the Provincial Diwan, a Mansabdar in his own right, independently controls the revenues of the province under the Imperial Diwan. Under them is the Bakhshi (paymaster), and the Diwan-I-Buyutat, the provincial representative of the Mir Saman who is responsible for the upkeep of the infrastructure and karkhanas (state industries) of the province. Lastly, the Sadr and the Qazi are entrusted with religious, educational, and judicial duties. This is all basically a smaller-scale version of the overall Imperial government structure.

In parallel with this a ruling council, the Panchayat-i-Subah, advises these officials, and can put forward ideas and also veto the actions of the officials. The members of the Panchayat-i-Subah are selected by a process of random selection (sortition) from the different Panchayat-i-Sarkar within the Subah. This process is used to avoid problems arising from class, caste and so on, as well as to remove the possibility of bribery being used to affect the selection of members.

Under these the region has a set of Mansabdar officials representing all branches of state activity. These Mansabdars are normally transferred from place to place across the entire Empire over the course of their careers.

[Note that although the names of the administrative groupings used within the Mughal Empire may be the same as those used historically, by the present day their structure and functioning is very different to that of the original groups. This is in much the same way as the structure and functioning of the British Parliament of the real world in the present day is very different to that of the British Parliament in the seventeenth century.]

SARKARS

Each Subah is subdivided in districts known as Sarkars. As at the level of the Subah, each Sarkar has its ruling council, the Panchayat-i-Sarkar, whose members are selected by sortition from the members of the different Panchayat-i-Pargana within the Sarkar.

Other important provincial officials are:

- The Faujdar, the administrative head of each Sarkar (district), who is appointed by the Emperor but under the supervision and guidance of the Nizam (governor). The Faujdar combines the functions of a district magistrate and superintendent of police, arbitrating disputes, keeping of the public peace, and recruiting military forces when necessary.

- The Kotwal, a city governor appointed by the central government to provincial capitals and other important cities. The Kotwal is the pivot of urban administration and performs a number of executive, judicial and ministerial duties, among which are a duty to prevent and detect crime, regulate prices, and in general be responsible for the peace and prosperity of the city. The Kotwal is personally responsible for the property and the security of the citizens of the city they govern, and in the case of theft must either recover stolen goods or be held financially responsible for their loss.

- The Mir Bahr, who performs the role of Port Commissioner, with additional powers over customs.

- The Amalguzar, who administers the finances of each Sarkar.

PARGANAS

Each Sarkar is divided in turn into Parganas. In the countryside a Pargana consists of a number of villages; in cities it is a district with a population roughly equivalent to a number of villages. These Pargana are run by a ruling council known as a Panchayat-i-Pargana. These deal with local disputes and administration and as with the Panchayat above them have members selected by sortition from the Panchayat below them, in this case the village-level assemblies known simply as Panchayat.

Most villages (or equivalent area in a city) have a Panchayat (ruling council) headed by a Sarpanch. The Mughal Empire interferes very little with the local life of the village communities. Each village also has a Patwair (accountant) who is responsible for the maintenance of the financial records and who is an employee of the village, not of the revenue administration. The Patwair is also responsible for arranging and implementing taqavi (loans from the state) to villagers to help with their needs.

PANCHAYATS

All the Panchayats in the Mughal Empire grow up from the local level, where Panchayats form village councils. Each level of Panchayat above this has members selected from the level below it selected at random from the eligible population (originally only the nobility, but now including all of the population of the region), by a process of Sortition, for the same reasons as for the Panchayat-i-Subah.

Each Panchayat has its own leader, the Sarpanch (known as the Sarpanch-i-Pargana, Sarpanch-i-Sarkar, Sarpanch-i-Subah and Sarpanch-i-Doulat respectively), and is effectively a lower house for the region they serve. It can propose, debate and approve legislation at its level, although the implementation of such depends on the approval of the local governor who along with their advisors form an upper house. Panchayats at different levels are not just legislative, but like the village-level councils they are derived from they are also judicial and arbitrate disputes brought before them. For the Mughal Empire as a whole the Durbar becomes the upper house. 'Villages' for the purposes of Panchayat representation also include village-sized districts of towns; these are periodically recalculated as population changes.

The Sarpanch of each council at every level is separate from the Kotwal and the Qazi of each area and level. As the system has developed over time these three positions have come to form a triumvirate of leaders, covering military/police, religion and the people/politics.

Because of the way the different councils are selected, with at the lower level people selected because people know them personally, and those in the councils above that are selected by Sortation from below, there are no political parties as such. On the other hand there are interest groups with common interests that cut across and up and down the councils.

The frequency of village elections are determined at the local level by the same processes that have been used since time immemorial. The sortation for the higher level councils take place every four years.

Free education is provided to all children by the Mughal Empire. Based on the unified Dars-i-Faridiya curriculum of Farid Khan Astarabadi which was first used in 1702, this provides a sound basis of knowledge, covering grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, logic, scholasticism, religious studies (covering all the major religions of the Mughal Empire), mathematics, history and the natural sciences.

There are a number of world-renowned universities in the Mughal Empire. In particular the universities of Delhi, Kabul and Agra are very well-respected. In addition to this the Mughal Empire has a number of astronomical observatories in Tibet. The University of Lhasa is especially well known for its astronomy department.

Taxation in the Mughal Empire is relatively simple in its theoretical formulation, though elements of it are complicated by changing needs and local circumstances. Both revenue and expenditure are divided between the central and the provincial governments. The Mughal Emperors have consistently attempted to keep the revenue system operating in as fair and equitable a manner as possible.

The central government reserves land revenue, customs, and profits from the mints, inheritance rights, and karkhanas (state-run industries) for itself. Land revenue and profits from the karkhanas are the most important sources of income; land revenue is based on detailed survey assessments updated at regular intervals, the nature of the crops grown and the current mean market prices, and also varied so as to encourage wasteland to be cultivated. The principal items of expenditure for the central government are defence, the administration of the Empire, including its religious organizations, maintenance of the Royal Court and the Royal Palaces, and the cost of civil buildings and other public works.

Provincial sources of income consist of revenues distributed by the central government as well as a variety of local taxes, transit dues and duties, and fines. Presents to officials are considered to be bribery, and so are illegal.

There are a number of large banks in the Mughal Empire, the modern incarnations of banks set up in the past by Hindus, Jains and Muslims. These all run under differing religious principles, though their customers are usually of all religions.

There are a large number of Tayefe Karkhanas ['Family industries', much like the Japanese Zaibatsu of the real world] in the Mughal Empire. These are, in general, expansive family-controlled banking and industrial combines, large companies that consist of divisions of often seemingly unrelated businesses. The largest of them - among them Tharoor-Pant, Matondkar and Roshan-Yagnik - control more industrial and financial power than some of the smaller nations of Gurkani Âlam. Because the Mughal government does its best to encourage and nurture business within the Empire, these exert a considerable amount of power in the Empire. However, because there are many of them, with different viewpoints and corporate philosophies, they do not control the government, and have much less influence than (for example) the Great Three in the Anglo-Danish Empire.

Although a good deal of Mughal industry is concentrated in its towns and cities, much of it is also distributed across the countryside, so that in many regions towns and cities are mainly military and political centres rather than manufacturing or centres of commerce.

Mughal and other Indian goods and products have long been, and continue to be, sold around the world. The Mughal Empire is a world leader in most fields of industry, science and technology, with its karkhanas [companies] buying and selling around the world. [Without Aurangzeb, and without the European takeover of India, India as a whole and the Mughal Empire in particular has remained industrialised and prosperous.]

The infrastructure of the Mughal Empire suffers from a lack of standardisation as the different Tayefe Karkhanas have built to different standards and ideas in electrical voltages, communications methods, railway gauges and so on in different places. Despite attempts by the Mughal government to rationalise/unify all of its infrastructures, this has met with limited success and so different standards still apply in different places in the Empire.

There are a number of different railway networks in the Mughal Empire built by different Tayefe Karkhanas, with government involvement in some of the more strategic lines. Many of them were forced to a standardised gauge at some point early on, and others have change to this gauge over time out of convenience, but there are still a variety of railway gauges in use in the Mughal Empire, a majority of them on private lines. Many of the railways follow the routes of the major roads of the Empire, such as the Grand Trunk Road. Because of this mixture of railway systems, the extensive Mughal road system has remained the main routes of long-distance transport in the Empire with, in a few places, canals also being used. The major rail connections within the Mughal Empire run between:

Delhi - Agra

Delhi - Varanasi

Delhi - Karachi

Delhi - Rawalpindi - Kabul - Samarkand

Delhi - Dhaka - Mandalay - Kunming - Chongqing - Xi'an

Delhi - Kabul - Tehran - Baghdad

Delhi - Kathmandu - Lhasa

Inside cities trams and elevated trams are the main form of public transport, normally with a gauge comparable to that of the railways of the region. They are used partly because of the expense of underground railways, though some of the major cities of the Empire, and Delhi in particular, have extensive underground railway networks.

The military of the Mughal Empire is a single unified system some six million strong. There are no separate services (such as the army, navy and air force); all military personnel are part of the same organisation. Rotation of military Mansabdars through different parts of the military has helped to ensure that barriers have not grown up between them. Although there are subdivisions within it, those between (for example) the army and the navy are no greater than those, for example, between (in the real world) the infantry and the artillery.

Mughal law enforcement is also military via the Mansabdars, but again a different specialisation. They form an armed Paramilitary force. Law enforcement Mansabdars make up roughly half of the Mughal military. Mansabdar-based law enforcement is not used to keep a larger standing army than might otherwise be the case; law enforcers are not intended to be soldiers, as this has the side-effect of law and order breaking down as soon as a war starts. However, they can and do act as a military reserve in case of need.

Like law enforcement, the Mughal intelligence services form part of military via a specialisation of the Mansabdars.

The Mughal Empire is mainly a land power, not a naval one. This is one of many reasons why there has long been conflict between them and the Holy Russian Empire. However, the Mughal Navy is a force to be reckoned with, capable of operating anywhere in the world, against any opponent. It is strongest close to India however, where its ships are used for local defence and patrolling.

Because of the history of these groups as warriors and members of warrior castes, many of the military of the Mughal Empire are Sikhs, Charans, Kshatriya and Rajputs, although with the Long War citizens of all kinds and social groupings became part of the military. All of these groups in particular are well represented in the Mughal elite and special forces. [Without Aurangzeb to alienate groups such as the Rajputs, they have remained loyal members of the Mughal Empire and its military down the years.]

The aim of the Mughal judicial system is primarily to settle individual complaints and disputes rather than to enforce a legal code. Altogether this system, combined with a general prejudice against litigation, and a large number of disputes, particularly those affecting Hindus, being settled by the Panchayats (councils) and not coming before the official courts at all (though this is not forbidden if necessary), results in comparatively few cases coming before the courts.

For those cases that do come to court, the Mughal judicial system is very simple. It has two types of judicial courts - the secular and the ecclesiastical. These are presided over by the Emperor (technically at least; in reality the Imperial Durbar performs this role), the governors, and other executive officers depending on the level at which the action is brought. The Qazi, being the repository of Muslim law, attends the hearing of cases by all executive authorities, and assists them in arriving at a decision in keeping with Koranic precepts. Judicial procedures are defined by the central government and applied uniformly across the Empire. Random checks by Mansabdar inspectors ensure that the system is applied as it is intended and that corruption is kept to a minimum.

As it has been since the days of the Emperor Akbar, the Mughal Emperor is the final religious authority in the Mughal Emperor, ruling on any religious disputes which reach the level of the throne, in accordance with the Koran and to the benefit of the Empire, and with the advice of members of all of the other religions of the Empire. The limitations of the Kabir Manshur (Great Charter) prevent this becoming the excuse for autocracy that it was in the time of the Emperor Akbar.

The secular criminal court is known as the Diwan-I-Mazalim (the Court of Complaints), and is normally headed by the local Kotwal. Normally no lawyers were allowed to appear in court. Because of this disputes are normally settled quickly, often on the basis of equity, natural justice, and local usage and custom though in the case of Muslims the injunctions and precedents of Islamic law apply where they exist. Many crimes, including murder, are treated as individual grievances rather than crimes against society, with the complaints being initiated by the individuals affected rather than by the police, and capable of being removed upon payment of sufficient compensation.

Apart from the secular courts and the Panchayats, the principal agency for the settlement of disputes among people of all religions is the Qazis' Court. This handles religious and civil cases, such as those concerning inheritance, marriage, divorce, and civil disputes. The Qazi arbitrates according to the canon law, though when both parties in a dispute are Hindus, the point at issue is normally referred to Hindu Pandits for an opinion.

It is possible for a defendant to appeal a verdict up through the judicial structure as far as (theoretically) the Emperor himself.

Fines are the normal mode of settling all disputes in the Mughal Empire. Humiliating an offender by parading them in public in an ignominious condition - in keeping with both Muslim and Hindu tradition - is also frequently used. Whipping and other corporal punishments are also common. Mutilation is sometimes used as a punishment. Imprisonment is not generally used as a sentence, though it is sometimes resorted to for preventive purposes.

The Mughal Empire does have the death penalty, but its use normally has to be confirmed by the Emperor and is uncommon. Executions can be cruel, and it is not unknown for impaling, dismemberment or crushing by elephant to be used. However, the cruel forms of execution are rarely used, and even then are confined to those cases where an example is to be made of the individual concerned.

The Mughal government has long placed emphasis on physical fitness and the encouragement of out-of-door games for everyone, to raise the general standard of health. The ideal is that all citizens should be trained to be a soldier, a good rider, a keen shikari (hunter), and able to distinguish themselves in games.

All towns and cities have publicly-funded hospitals, a system dating back to the fourteenth century and extended by many Emperors down the years. Most villages have a least a doctor on call.

The Mughal Empire possesses a fairly comprehensive social welfare system, but it is one only indirectly provided by the Mughal state. Instead, the Mughal welfare system is provided by way of the Gurdwaras of the Sikh faith. Originally providing free food and (sometimes) shelter to all comers regardless of race, gender or religion, over time, and with the rise of Sikh influence in the Mughal Empire the Gurdwaras have expanded the free services they provide to also include medical care and education. They have also spread across all of the Mughal Empire and beyond, into the rest of India, Asia and around the world. Although these Gurdwaras are partly funded by the Sikh people themselves, they also receive a great deal of funding from the Mughal Empire, in recognition of the great service they provide to it.

The population of the Mughal Empire is still growing, but slowly, as advancing medical technology and changes in society have caused people to have fewer children [not unlike the case in the West in the real world]. Some attempts to put population control measures into place have also been made, although so far with little impact.

All Muslim, Hindu and Sikh festivals are celebrated in the Mughal Empire, as well as most Christian, Jain and Parsi (Zoroastrian) ones. Governors and so on are expected to take part in all of these festivals for the good of the Empire, regardless of their own personal faith.

The Mughal Empire has a long tradition of Imperial and noble sponsorship and support of artists of all kind going back hundreds of years and continuing to the present day. The literate and refined Mughal court has long given a recognizable style and manner to a wide variety of arts. The most obvious area of this is in the field of architecture, where Mughal buildings such as the Taj Mahal, the Taj Jehan, the Pearl Mosque in the Red Fort, the Red Fort itself and so on continue to be known around the world for their beauty and artistry. However, there is also long-standing patronage of music, painting, literature, poetry, history and biography (particularly in Persian and Hindi, with some work also in Urdu, Bengali, Deccani, Hindi, Sindhi, Pushto, Kashmiri, and the other local languages of the Empire).

Despite the best efforts of Mughal Emperors since the time of Akbar, marriage in most of India generally takes place at a young age. Most girls are at least betrothed before the age of twelve, with this being arranged and negotiated by their parents, often with the help of their friends and/or a professional matchmaker. Hindus normally marry at this point, although the marriages may not be consummated before the wife reaches puberty. Muslims and others normally continue the engagement until the girl reaches puberty. It is generally considered best for both parties in the marriage if they are of roughly the same age, and not too closely related. Polygamy is common, normally depending on the ability of the married individuals to support a family of a given size. Divorce is also quite common, and easy to achieve.

Since 1804, when Princess Gertrude of the Holy Roman Empire became the first European noble to marry into the Mughal royal family when she married Prince Nikusiyar, the third son of Muhammed Akbar II, there has been a steady low level of intermarriage between the Mughal and European royal families.

As a side-effect of the Mughal influence on the world, the age of consent in many European nations remains considerably lower than in the real world, with ages from ten to thirteen considered acceptable. [That is, ages of consent in Western countries in this world are much the same as they were in the mid-Nineteenth Century in the real world.]

The upper classes of the Mughal Empire maintain the courtly manners and elaborate etiquette they have used for hundreds of years. In social gatherings they speak in a very low voice with much order, moderation, gravity, and sweetness. On the other hand, court life has a great deal of intrigue and cruelty as well as refinement of taste and elegant manners.

Betel and betelnut is presented to visitors when they arrive and they are escorted out with much civility at their time of departure. Rigid formal manners are observed at meals.

Alcohol a minority drug in the Mughal Empire, mainly used by Christians. Opium and marijuana are much more commonly used across all of society.

Dice is a favourite indoor game across the Empire, while polo or chaugan (a kind of hockey with the player on horseback), elephant and other animal fights, game hunting (shikar), high cuisine and wine, garden parties, excursions, pigeon flying (Ishqbazi), archery, horse riding and picnics are also very popular fashions for these, often filtering down from the Emperor himself. The richest of the upper classes drive the finest vehicles, sometimes themselves and sometimes chauffeured. These are often ornately decorated, normally with gilt and gold.

The games of Kabaddi, Carrom, Bull Racing and Sepaktakraw are very popular in India and have spread from there across the world.

The Hindu practise of sati (the immolation of widows) is banned in the Mughal Empire. However, it is not unknown for Hindu widows to take the bodies of their husbands into the Dakshina Nad, where sati is generally legal, and both burn their husbands and commit sati themselves there.

The religion of the Mughal Emperors is Islam, and there is no explicit separation of church and state in the Empire. However, the Mughal government is not associated with any specific religion, and members of all religions are well-represented within it [unlike the case in the real world where, in the Mughal Empire under Aurangzeb the increasing association of his government with Islam drove a wedge between the ruler and his Hindu subjects]. The powers that be of the Empire are largely content with outward signs of devotion. Thus the average citizen participates in public ceremonies in much the same way as they pay their taxes, as a civic duty that does not require any personal commitment if they are not so inclined. Outside of this they are free to devote their personal spirituality to whatever creed they wish so long as it does not interfere with public order.

All Mughal Emperors continue the Hindu-inspired practise of Darshan, or public appearances to bestow blessings, which has occurred since the time of the Emperor Akbar.

In all but the most severe crises there are lavish celebrations of the Emperor's birthday across the Mughal Empire.

By tradition Mughal princes marry Hindu women, normally from the Rajput caste. Mughal princesses are freer to choose, and can marry either Hindus or Muslims. This has been the case since Emperor Shah Buland Iqbal lifted the ban on them marrying in 1665 as part of the price he paid for assistance from his beloved sister Jahanara Begum during the succession struggle after the death of Emperor Shah Jehan, their father. As such Jahanara Begum was the first Mughal princess since the time of the Emperor Akbar (who imposed the ban) to marry, but not the last. Since then, most Mughal princesses have chosen to marry Hindu men, mirroring the marriage practises of their male siblings. This has all helped to increase inter-religious links and tolerance with the Mughal Empire.

The Mughal Empire uses both the Islamic Calendar and the Hindu Calendar, though a different variant of it to that used in the Dakshina Nad. The Sikh calendar is also widely used among members of the that faith, both inside the Empire and out.

The Hindu caste system still exists in the Mughal Empire, but has been weakened over time by social change, and particularly the actions of the Sikhs in educating those of all castes. As well as educating those of low caste, this has allowed people of those castes to see the unfairness and biases of the caste system and work to remove and overcome them. This weakening of the caste system has been tacitly supported by the Mughal Emperors down the years, despite violence from Hindus opposed to any change to it, and in particular by the appointment, in 1853, of the first person of the Untouchable caste to the Mughal Durbar by Mughal Emperor Shah Buland Iqbal II. By the present day the caste system in the Mughal Empire is no more a barrier to individual progress than the class system of real world present day Britain is to its citizens, with economic and social mobility being entirely normal.

The World in 2000 | Africa | Central America And The Caribbean | North America | South America | Antarctica

Central Asia | Eastern And South-Eastern Asia | South Asia | Europe | The Middle East | Oceania

Go to the Gurkani Âlam Timeline, Differences, Politics, Science and Technology, Society, Notes or Summary Pages.

Back to the Gurkani Âlam Home Page.

|

Copyright © Tony Jones, 2007.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. |